There’s an exciting theory going around at the moment. Maybe you’ve heard it. It says that we’re probably living in a simulation, because if it’s possible to simulate worlds, as to some extent it seems to be, then there will certainly already be loads of simulated worlds. At some point there will be far more simulated beings than there are real ones, and the sims won’t know they are sims, or where they ‘really’ are in space and time. Therefore the chance of us being one of the few originators, at the beginning of this process, is miniscule. We’re almost certainly sims.

It’s mind-boggling at the most fundamental existential level, just as it would be to encounter aliens, but setting the philosophical dazzle aside for a moment, these kinds of thoughts have to come from somewhere. They must be popular at the moment because they have some value in the here and now. (And, though I won’t go into it now, there must be a reason these weird ideas have particular success among Silicon Valley billionaires, too.)

One explanation for the appeal of the idea: it lends a grand context to our own modest attempts at synthesising things, which seem to be held back by the physical constraints of today’s technology. We have outsize hopes for our tech, partly because the only comparison we have for digital is speculative fiction, and relative to that, reality moves frustratingly slowly. It’s unlikely any of us will see substantial change within our own lifetimes, and every disappointment is a reminder of our own limits in time and space. Suppertime after suppertime passes without mind-controlled GM-meat floating across the table and into our mouths, and all the while, death looms nearer. The situation is desperate, and if hope is to be preserved, we must double down on our ethereal escape routes.

These ‘grand contexts’ contribute to our completely unsubstantiated impression of tech as other-worldly. There is nothing inherently mystical about digital, but of course, people buy the sizzle, not the steak. Surely the reason tech is so enormously well-funded is not because it is something, but because it represents something. It stands for the exciting ideas of open-ended potential.

This might sound harmless enough, but it really amounts to the most colossal opiate, and is a legitimate source of fear. Digital can get away with anything, so perhaps it’s not future sentient A.I. we’re worried about at all. Maybe, subconsciously, we’re twitchy about the values we’ve already put in the hands of digital. After all, it’s not just empowered, it’s virtuous! To call something progress is to imbue it with a moral compass. In permanently merging tech with progress, we’ve invented something that cannot be wrong! I can think of nothing more dangerous. And more and more of us are forced into service, not of the “robot army”, but of this monster we’ve created. We’ve decided its destiny is to be bigger and more awesome and more mysterious than we’ll ever understand.

I think one reason digital is so amenable to this kind of quasi-religious treatment is because it’s a constant act of speculation. Nothing we make with digital tools is guaranteed or secure, yet we’ve decided to try to use them for everything. The result is tremendous excitement, but also radical destabilisation. Digital is a tool or a solution – always a monstrous half-a-thing. We make, invest, even pray for the divine arrival of a purpose for an object, or an object for a purpose. We’re waiting, like the Panaceans, for something unaccountably more. We characterise ourselves (again like the Panaceans) as being permanently ‘on the brink’ of a major (tech) breakthrough. And we live happily in this brink-world stasis.

The singularity and simulation concepts, for me, sum up this ‘waiting’ life. If our efforts in digital can be associated with a much more important idea, they’ll bask in the reflected glory. But it would be a great shame to be proven wrong, so we suggest completely unfalsifiable ideas, to ensure we’ll always be waiting for the proof to arrive.

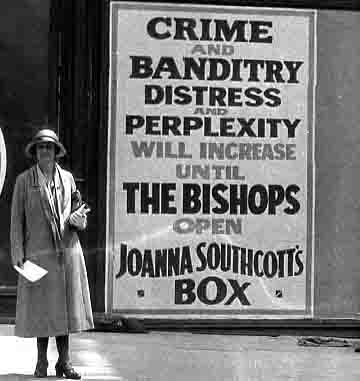

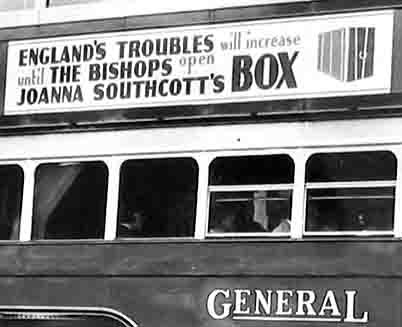

Another clue: we never let the end come. We might say it’s amazing that we have satellites and voice-controlled AI and Google Streetview, but do we really find it amazing? Still? We get used to weird, extraordinary things scarily fast, as though we want to keep weirdness at a tantalising distance. Something must always remain unresolved. Digital’s potential is one of our perma-mysterious things, a kind of 21st century cryptozoology. Because digital represents mystery and continual progress, we cannot allow it to arrive – ever. Like Joanna Southcott’s box, it gives meaning to our lives as a symbol of unfulfilled potential.

Just like apocalypse cults whose meteor collision dates pass without drama, we absorb the inconsistency of digital predictions into our mythology and let it go. It was never about the meteor, and it’s not about the tech.