The Power of the Literal

Some things don’t really look like what they are, like TVs and solar panels and paracetamol pills.

Other things kind of do look like what they are, like windmills and knitting patterns and paddle steamers.

Things that look like what they are often give us a bit of a warm feeling. Maybe this is why we’re so into them at this point in history. In my opinion, we’re in the middle of an age obsessed with literalness and ‘authenticity’. It’s always been a rare commodity, but for some reason (probably lots of complicated reasons), it’s the prize we’re particularly interested in at the moment. In the eighties we wanted money; in the nineties through to the noughties we wanted fame, and now, in the age of fake news, bare lightbulbs, twitter ticks and Wikileaks, we want transparency, and we look for it everywhere.

The currency of technology is not transparency. Digital culture’s influencers hold a prism to the truth and filter it, in the way that all cultural drivers do, but a thousand times more powerfully because technology chiefly brings amplification. Digital products are also travelling away from transparency, shrinking and hiding their true workings. And the more they mystify themselves, the more they pump up the value of technical knowledge.

We have what I call a ‘magic mirror’ problem right across digital culture. From physical hardware design to social media trends, commercial tech is dragging us away from the uncomfortable honesty of the literal and into a bizarro world that only ever shows ourselves and our lives as a glossily perfect dream, filtering out any evidence to the contrary.

That’s not really a new observation, but I’d like to go further. I think digital culture’s demand for perfect imagery about our lives is linked to the pristine, opaque design of consumer tech – machines that can only be opened by the annointed ‘Genius’ at the Apple store. (Oh, you came to the Panacea Society blog to find out about a sealed box full of mysteries and future promises? What do you think you’re reading this on?)

Transparency is next to literalness. Things that pretend to be other things can be fine and innocent, but contemporary tech is angled towards deception in order to sustain a particular status quo. There’s so much money involved, it would be naïve to think any other significant forces were getting a foot in. And we’re part of the problem. We rather like things that are shiny and impossible to open, they make us feel like there’s still mystery in the world.

It might seem like faith is about pretending, in a ‘fake it till you make it’ kind of way, but the opposite is surely just as easily the case. The point of joining up to an organisation like the Panacea Society is not to invent but to find the truth, according to what works. And the Panaceans, brilliantly, were genuinely interested in what works. They were halfway to being scientists, collecting data on their healing squares, encouraging honest interactions with their community, a door always half open to the possibility of answers from outside.

They were quite a geeky bunch, I think, and very businesslike. Their approaches to problems were so specific and practical they’d make today’s productivity gurus proud. Their public petitions – including enormous adverts on buses and in major London billboard sites – are striking for a religious movement because they weren’t a recruitment drive or a promise, but more like an Oxfam appeal to buy medicine: “Here’s the cure, and all we need is one simple event to make it happen. How can you stand by and watch these social ailments fester when there exists a clear remedy?”

There is an innocence to it all that we just don’t see in digital – at least not in the digital we’re used to seeing. Literalness is charming because it’s innocent and strict at the same time, and I look for the places where digital finds that sweet spot, where it’s just as it seems: light, movement, on and off, black and white. It’s rare, though, to find approaches to tech that are insulated from the nuances of culture. From robots taking our jobs to Bitcoin using more power than the world can supply, when digital mixes with human frailties it is as much the apocalypse as the cure.

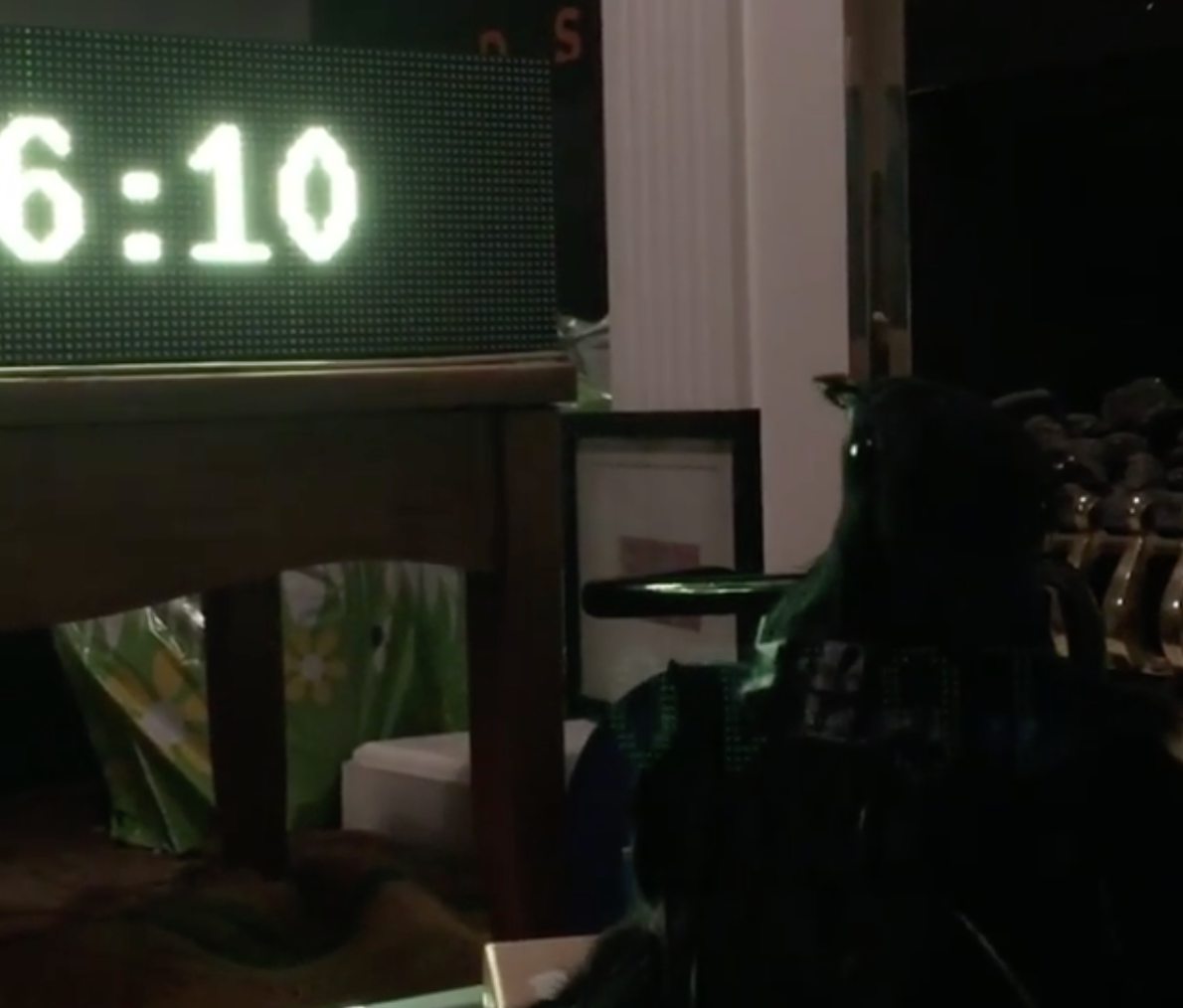

Maybe it was my pixel stuff that got me onto that, this week: a pixel per LED, a colour for a light, it’s just as it seems and nothing is lost in translation. I’ve been working on new digital animations for the apocalyptic cuckoo clock (see screenshots in this blog post) and am now running a real clock on the screen between them, to I think very pleasing effect. In the final version the clock will run all day with the graphics appearing infrequently (probably not just every hour, Atmosfear is a definite influence), but for now I’ve got them coming on every few seconds on a cycle. Feel free to ignore the KLF soundtrack, though I feel it adds a certain something?!

https://www.instagram.com/p/BcnjF4OHXuv/?taken-by=hackingrambert

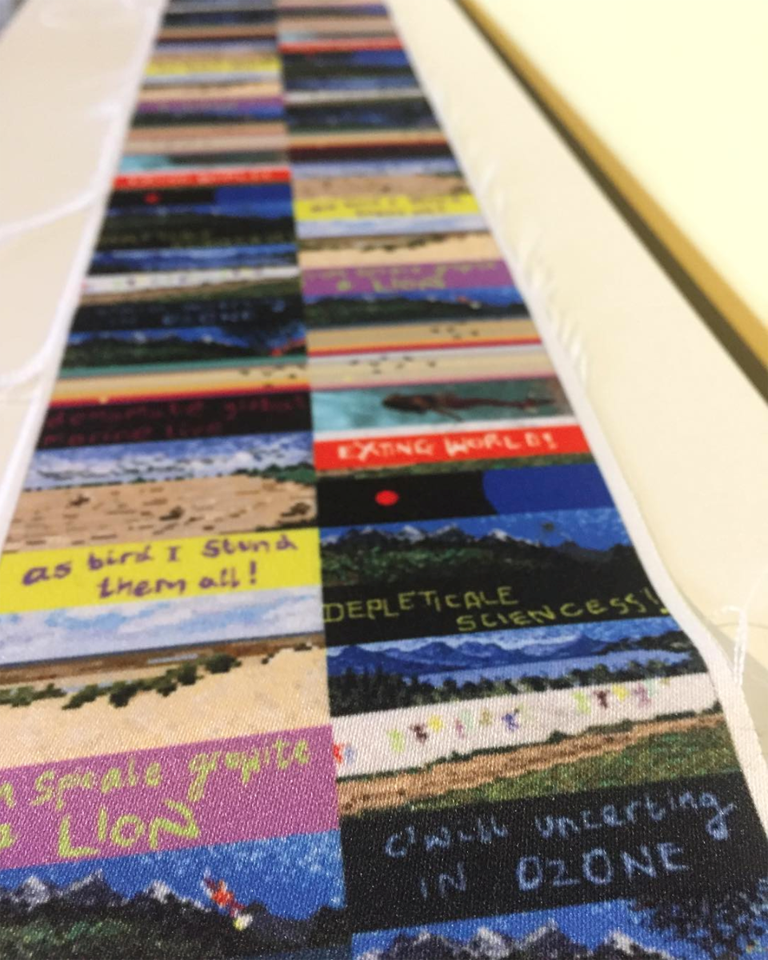

Also this week, I’ve had a length of satin printed with some of these graphics. This follows on from last week’s thinking about creating a new kind of science-faith, or religious-pragmatism, inspired by the Panaceans and the ideas about AI that I’ve been handling on this residency. I’m going to attempt to make some symbolic garment for my new faith-sci (really need to come up with a better term for it…. mystic-Sci-sm?) The silk looks lovely. To find out what I do with it, tune in around the middle of next week.

Finally, I’ve started creating a little book as an outcome of this residency, based on these blog posts and other things. For an idea of how it might come out, see the book I created on my Rambert residency in 2016.

Next time: more graphics for the clock, perhaps audio too, and a mystic-SCI-sm garment (and better name, possibly).