I am glad to add further voice to the debate on the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s pasting of the 95 Theses at Wittenberg Castle which spurred what we know today as the Protestant Reformation.

I cannot but thank the organisers for the opportunity given me to participate in the just concluded CenSAMM Symposia Series 2017 conference, 500 years: The Reformation and its Resonations, held at Bedford, UK.

My paper titled, Luther versus Us: Encountering the Reformation through the Eyes of an African Class, was met with huge reception and the intellectually engaging questions asked in the subsequent discussion has opened even further scholarly interrogation and enquiry for me to work on.

Luther remains until today a very complex figure which is understandable. Religion, as Karl Marx observed, is the opium of the masses. Marx’s suggestion of religion as masses-centred may have been right in the 19th and 20th centuries, but it was simply not so in the time of Martin Luther and centuries before. Religion was simply the opium of the Catholic Church heralded by popes and clergymen.

It is assumed, as many are wont to agree, that when the Church sneezes, the European population catches cold. It is why even as European peoples kept their belief and faith in the Church; the latter busied itself with infighting and divided its headship into three distinct authorities. By the time it had found some amicable solutions, it was hit by ‘stumbling blocks’ from which the Church is yet to recover from.

One could, therefore, understand why Luther is perceived as a complex figure. His actions, as we know it, knocked out the religious centre of authority in Europe and challenged a very powerful institution that had seen itself as unchallengeable. We are yet to understand why it wasn’t in the era of John Wycliff or Jan Hus that the Reformation was sparked. Both men vehemently condemned the Church for its corrupt tendencies and readily preached that Christ and not the Pope was the true head of the Church.

When we take a critical look at the 95 Theses and a handful of what Luther preached in the aftermath of the 1517 Reformation, we would see that he did or said nothing new and so, questions continue to rage on as to what Luther did differently to have helped his cause. In any case, there is a notion that Luther had ‘revolted’ against the Church at a time political forces incidentally also had pent-up grievances against the latter. The fact that Elector Prince Frederick III of Saxony, for instance, gave Luther express protection (which Wycliff or Hus never enjoyed) may also explain why his ‘mission’ to reform the Church prevailed even against all odds.

Indeed, and quite sadly, not many in Africa have sufficient grasp of this period in European history.

Since the dearth of teaching history (which often comes at the tertiary school level) in Nigeria, few who stumble on history do so by chance. If you are not admitted into a history major, there is the likelihood that you may not be offered European History. While many may argue that the teaching of this ‘foreign’ history is not beneficial to Africans intellectually since there are a handful of African history courses yet to be taught, I find such belief faulty.

Africa shares a deep history with Europe and one of the direct consequences was the spread of Christianity. While it is discussed in hushed tones, we know today that Africans are now even more Christian than the Pope and Luther. I think it was Jacob Olupona who called it “reverse missionary”. Why this is so is not even much of the influence of Christianity but the process through which the religion arrived on the continent.

It was a sort of good thing that not only the History but also English and French Departments offered European history and despite our initial apprehensions as freshmen, we learnt a great deal.

The Reformation class was, indeed, intellectually stimulating and fascinating as well. A significant portion of the class thought Europe in its present state was the same in time past. The Reformation, therefore, cleared the air about this notion. If there were incidences of religious disputes in Africa today, Europe too had had it not once or twice. But beyond this reality, our encounter with Luther and confrontation with the Reformation threw up vast amount of critical enquiries that stuck mid-air. These were some of the issues I tried to raise at the conference and also provide satisfactory response to.

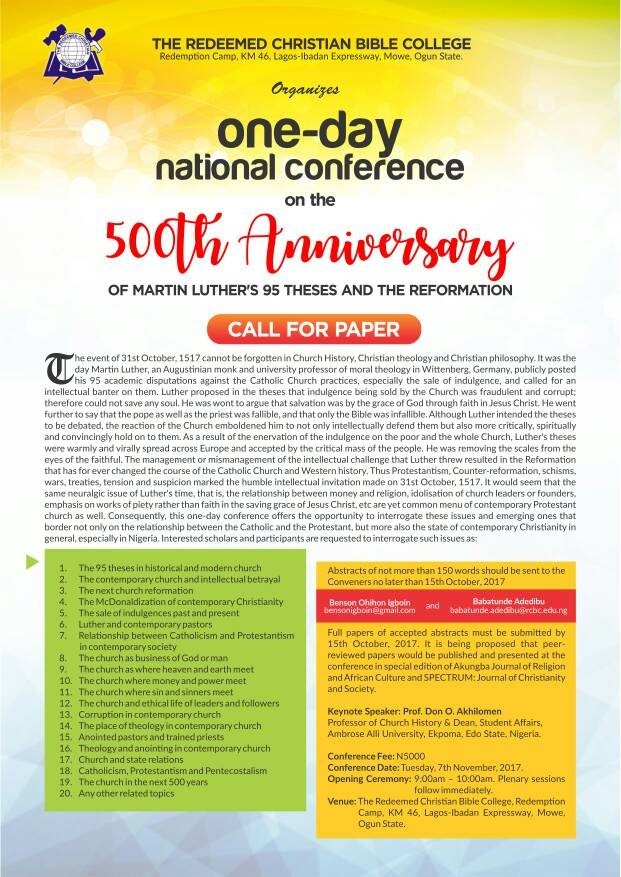

For an event as seismic as the Reformation, and for reaching 500 years, it would have been thought that academic institutions or Christian bodies in Nigeria would pay much attention to it. None to the best of my knowledge appear to have hosted or will be hosting a conference, workshop or even a call for paper for a book or journal publication except very few such as this:

The Reformed Baptist Church in Nigeria held a weeklong programme in January this year to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. The Church’s Facebook page also indicates it will host the event throughout this year with an Anniversary Service at the end of October and in November. Not surprisingly, local newspapers have not been receptive to this event.

I happened to, however, stumble on an excellent piece surprisingly published in 2016 (and not this year, 2017) in one of the popular local newspapers. It goes to show that the Reformation is rarely known and this, as we see, is the fallout of the absence of teaching European history to a wider Nigerian student audience.

As the Reformation reaches the 500 year landmark, it is hoped even more lessons will be learnt in Christendom and indeed, among followers of other faiths. Irrespective of Luther’s failings, his sincere actions challenges us to speak for religious justice and fairness in an age lacking in one.

Raheem Oluwafunminiyi was a Research Fellow in the just concluded 5-Year (2012-2017), €1.5 million European Research Council sponsored project on “Everyday Religious Encounter in Southwest Nigeria”. He was also a Teaching Fellow at the Department of History, Adeyemi College, Ondo, Nigeria. Raheem’s research interests cover such areas as African Spirituality, Sermon Studies, Political History and Latin American Development. He is currently undergoing his Doctoral Programme at the University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria.