Avant-garde art has long been considered a bastion of secularity, holding strong against the creeping return of religion in contemporary culture. But in fact elements from ancient Apocalyptic narratives remain inescapable undercurrents in the work of a surprising number of contemporary artists. Tropes associated with Apocalypse shape current discourses about climate change, AIDS, racism, geopolitics, war, greed and materialism. Artists pick up on these, using myths and metaphors associated with the Apocalypse to help us understand the deeper structures of our thinking.

Among the most powerful of these tropes is the Grand Battle of Good and Evil. According to the Book of Revelation, mankind is caught between two supernatural forces whose engagement will inevitably result in the catastrophic end to human endeavors and the ultimate triumph of righteousness, justice and truth. In today’s idiom, that battle has been reworked as the Clash of Civilizations. American leaders from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush to Donald Trump have shaped their foreign policy around the idea of a grand battle between the Democratic West and an Evil Empire, whether construed as Soviet Russia or the Islamic State. In the Islamic world, Osama bin Laden and ISIS have reversed the terms while leaving the apocalyptic dualism of a Holy War in place.

Artists with a historical bent complicate this apparently simple scenario. Drawing on myth, fantasy and ideology, they reveal the degree to which “true stories” and “realpolitik” are conditioned by ideas embedded in apocalyptic literature. For instance, the Book of Revelation maintains that the final battle of good and evil will be preceded by the rebuilding of the Third Temple of Jerusalem. Israeli artist Yael Bartana uses this as the basis for her cinematically spectacular 2013 video Inferno. Invited to do a project in Brazil, she discovered that an evangelical Christian group was rebuilding the prophesied Third Temple in the city Sao Paulo. Bartana used the plans for this new Temple as a template for her own version. Built like a stage set, it provides the destination for a videotaped procession of Brazilians garbed in white and sporting Carmen Miranda style headgear through the city.

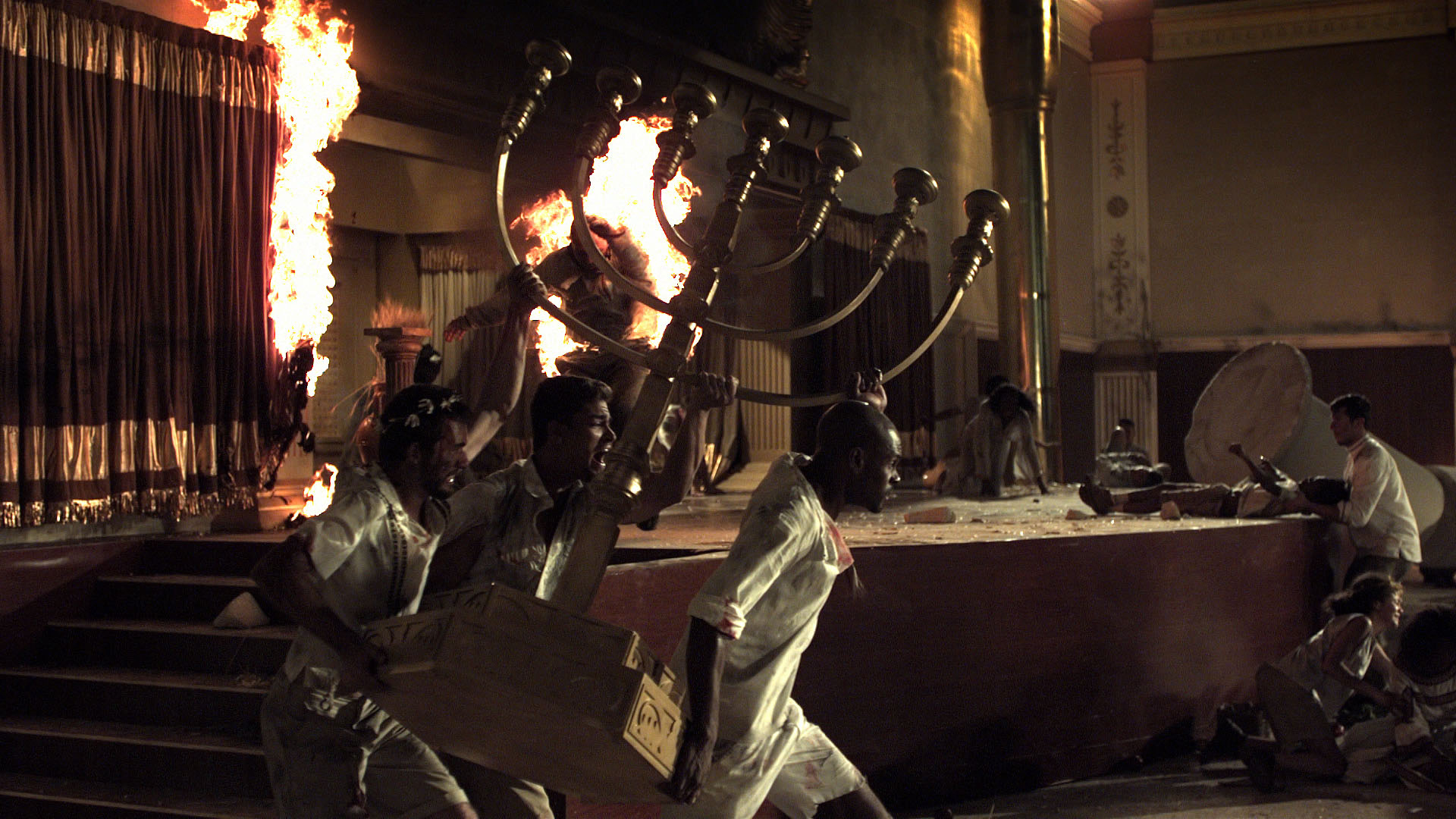

Once at the Temple, the performers celebrate the new construction, presided over by Marcia Pantera, a famous Sao Paulo drag queen who assumes the role of high priest. The joy of the faithful is short-lived as the Temple is beset by fire and earthquake, finally crumbling around the participants in a conflagration worthy of Hollywood. The film ends at the Wailing Wall, a rebuilt remnant of the Second Temple in Jerusalem that serves now as a Jewish pilgrimage site. In Bartana’s video, characters from the Sao Paolo celebration, including a Christ-like figure in ancient garb, wander among the present day tourists and worshipers.

Playing with historically inspired hopes and fears, Inferno acknowledges the Temple’s multilayered symbolism. The participants’ mix of races reflects both Brazil’s ethnic diversity and the hope for universal salvation embodied by the local Christians who are somewhat absurdly rebuilding the Temple in Sao Paolo. The apocalyptic denouement of the video is subject to a variety of interpretations, as is evident from the responses of different audiences. In Brazil, blogs denounced the “gay movie about destroying Solomon’s Temple in Brazil”, a reference to the presence of Marcia Pantera. Germans saw the video as a reference to Kristallnacht. Jews in the United States saw it as a statement about the impossibility of rebuilding the Temple. In Israel, the main reaction seems to have been confusion, reflecting perhaps the similarly confused debate over the present and future disposition of the Temple Mount itself. Playing with fact, fiction and myth, Bartana reveals how the same history gives credence to religious “truths” that directly contradict each other.

Jerusalem reappears as a contested site a three part video epic by Egyptian artist Wael Shawky. His Cabaret Crusades takes as a point of departure Amim Maaalouf’s 1984 revisionist history The Crusades through Arab Eyes. Like that book, his elaborate videos offer an alternative version of the “clash of civilizations”. In Cabaret Crusades the Christian narrative of the Crusades as a war to reclaim Jerusalem from the Muslims is replaced by a much more confusing history marked by a complicated series of shifting political and religious alliances and conflicts.

In the three films, each of which was commissioned by a different presenter, puppets move through elaborate sets beneath a voiceover script in classic Arabic. The films’ focus on actual history complicates the narrative of good and evil as told by both Christians and Muslims. Far from documenting a unified offensive against the enemies of the faith, the films reveal individual leaders making dubious alliances in an effort to advantage themselves. There are moments when Shias and Sunnis fight each other or ally themselves with the Franks, and others where Christians turn on each other. Together events suggest that betrayal is the common currency. Questions of faith appear as pretexts for otherwise inexcusable actions. In the midst of bloodshed and atrocities that seem to echo current conflicts in this part of the world, the worst and best of human nature are on display. Saladin, Sultan of Egypt and Syria, provides a model of religious tolerance toward the Christians, while the Doge of Venice is a symbol of expediency as he makes multiple promises that he can’t possibly keep. Enacting these events with puppets allows Shawky to suggest a world in which people are subject to forces beyond their control. These forces, he suggests continue to reverberate through the conflicts of our own time.

Both Bartana and Shawky suggest how inextricably the apocalyptic narrative is entwined with our understanding of history. Jerusalem here ceases to be an actual city and becomes the mythic prize and proof of competing religious belief systems. These in turn seal its fate in a cycle of never ending conflict. These artists ask us to rethink the tendency to justify sectarian war and conflict as the inevitable consequence of a pre-ordained battle of Good and Evil. In doing so they reflect the warning issued by critic Frank Kermode. In The Sense of An Ending, his brilliant adaptation of eschatology to literary theory, Kermode maintains, “. . .a myth, uncritically accepted, tends like prophecy to shape a future to confirm it.”[1] Bartana and Shawky remind us that the apocalyptic narrative has consequences that continue to shape our reality.

[1] Frank Kermode, The Sense of an Ending, Oxford University Press, reissue, 2000, p. 94.

Eleanor Heartney is a Contributing Editor to Art in America and Artpress and has written extensively on contemporary art issues for such other publications as Artnews, Art and Auction, The New Art Examiner, the Washington Post and the New York Times. She received the College Art Association’s Frank Jewett Mather Award for distinction in art criticism in 1992. Her books include: “Critical Condition: American Culture at the Crossroads” 1997, “Postmodernism” 2001 “Postmodern Heretics: The Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art” 2004 (reissued 2018), "Defending Complexity: Art, Politics and the New World Order", 2006 and “Art and Today”, a survey of contemporary art of the last 25 years from Phaidon, 2008. She is a co-author of “After the Revolution: Women who Transformed Contemporary Art”, 2007, which won the Susan Koppelman Award. Heartney is a past President of AICA-USA, the American section of the International Art Critics Association. In 2008 she was honored by the French government as a Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.