In an email several years ago, roboticist Hans Moravec wrote to me that he was too busy making the future happen to have time to talk about it. Moravec—a critical figure in the history of mobile robotics and the author of Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence and Robot: Mere Machine to Transcendent Mind—had left Carnegie Mellon University and was employed by Seegrid, a start-up company designing robots for work in warehouses. In addition to his seminal research into robot navigation, it was Moravec who put a decidedly scientific gloss upon science fiction futures, arguing that technological trends prove that in just a few decades our computers will vastly outstrip human intellectual powers and that we will upload our minds into robot bodies to remain competitive with the godlike machines. Moravec’s career reveals two possible strategies in bringing about a digital apocalypse: writing prophecies and building next generation technologies. Does revealing the newest gadget do more to usher in an apocalyptic future than writing about it? Probably not.

In his books, Moravec argued that progress in digital technologies worked according to an exponential logic that would produce—in just a few decades—machines whose capacities were many orders of magnitude beyond our own. We will, he claims, upload our minds into machines and join our technological progeny in a beautiful new universe of meaningful computation. Influenced by Arthur C. Clarke and other science fiction authors, Moravec first published his argument in a 1978 article in the magazine Analog and then elaborated upon it in his books, published in 1988 and 1999. In these books, he argues that the transition of biological life to digital life is a natural outcome of Darwinian evolution. While Moravec is less famous than other futurists, he was the seminal scientific thinker behind the 21st century belief in a radical machine future. In 2018, however, his vision appears little closer than it did in the 1980s. While this apocalyptic vision of AI has accumulated widespread interest, neither his brilliant books nor those of authors who adopted his vision and advanced it have made the apocalyptic transition to machine life very likely.

Perhaps this apocalypse-later owes its delay to problems inherent in writing prophetic books (i.e. “futurology”). In a recent book, The Future (MIT 2017), digital media artist and scholar Nick Montfort proposes that “future making” is distinct from mere futurology because future making is contextualized within actual working systems. Douglas Engelbart’s oN-Line System, for example, was based on novel technologies (e.g. the mouse) and was situated within the working needs of actual people. Engelbart’s work pointed toward what would eventually become the Internet precisely because it was an actual technological configuration that appropriately matched relevant social (workspace) conditions. Future making, Montfort suggests, actually works.

Prophets of the digital future also attempt Montfort’s future making. Moravec worked at Seegrid, after all. His popularizer, Ray Kurzweil, works on AI at Google. Seegrid, unfortunately, went bankrupt. But Kurzweil—justly famous for inventing OCR, reading devices for the blind, and music synthesizers, and more recently for his adopting and championing Moravec’s view of the future in books like The Age of Spiritual Machines and The Singularity Is Near—grabbed the post of Director of Engineering for Google. In that position, he’s leading the team that seeks to augment human email communication by making suggestions for quick replies to emails. While his authorship of The Singularity is Near is clearly futurism or futurology, perhaps his work at Google is future making; after all, there’s a real product involved, and that technical artifact is part of wide-ranging human systems of communication. So perhaps it means that we’ll all soon fall in love with our operating systems (as suggested in the movie Her) and shortly thereafter see the departure of transcendent artificial intelligence for the furthest reaches of the galaxy.

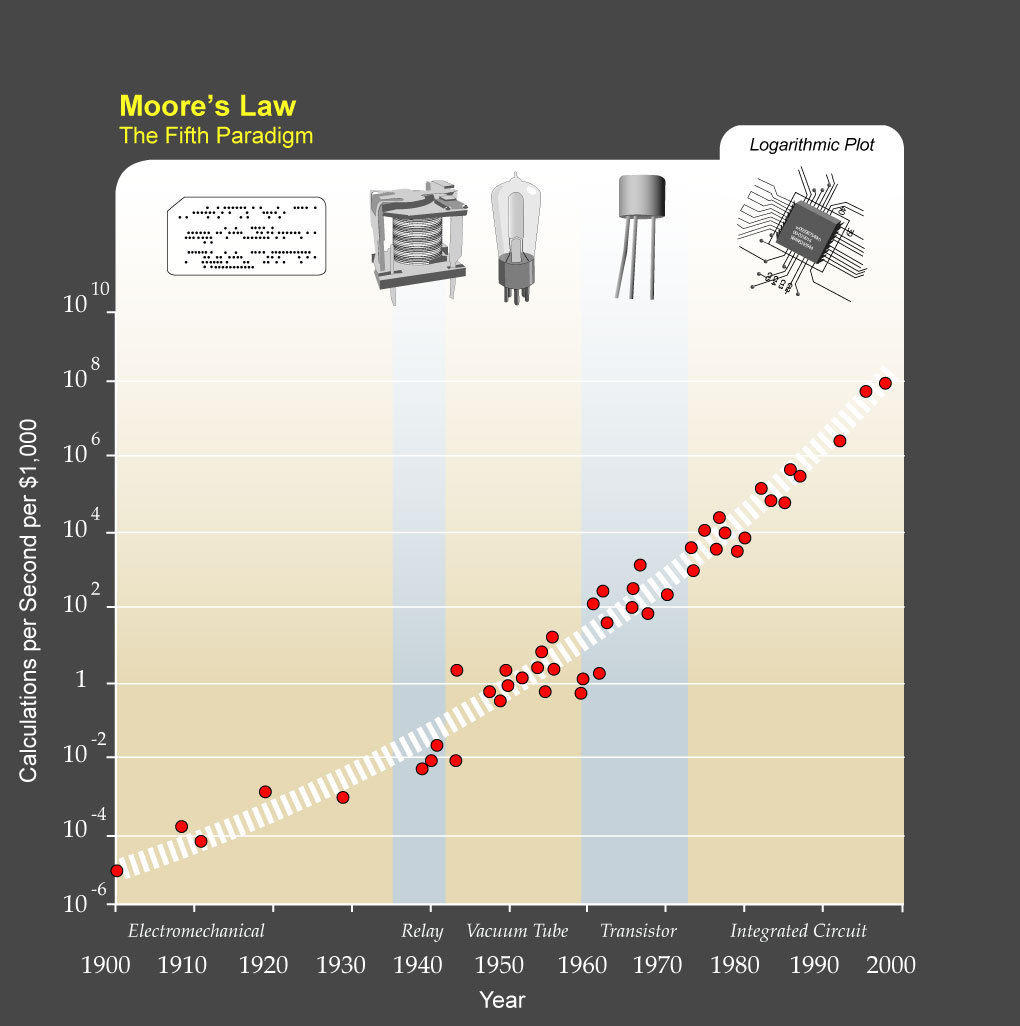

I’ve shown the deep connections between prophecies of a robotic future and prophecies of a religious future in my book Apocalyptic AI: Visions of Heaven in Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, and Virtual Reality; and these connections call into question the likelihood of transcendent machines and immortal robot bodies. One might suggest through such a comparison that the prophet is unlikely to see the transcendent new promised land. After all, no apocalyptic vision of the future has yet come true, so what reason do we have to believe in these latest promises? Kurzweil and Moravec point to actual technological achievements and past developments as evidence for a trajectory that predicts the future. On the face of it, this is at least more promising than asserting one’s nighttime vision accurately portrays the imminent doom of the world. After all, the technological progress is quantifiable. One can chart out the improvements in digital software and hardware, then simply assume those improvements are indicative of technological trends to come. Move along your graph of increasing computational speed or efficient robot vision and you can smoothly transition from the awkward past of robot vacuums that tumble down stairs to the glorious future of robot minds that sail interstellar space.

Kurzweil, especially, is fond of charting progress in processing power and other technologies, but these extrapolations cannot account for future surprises and fail to consider hard economic realities. Perpetual (even long term) exponential growth is impossible to sustain; but let’s put that aside. Let’s not worry about the limitations to resources—from bandwidth to metals in the ground—that place restrictions on reality. Let’s not fret over whether Mind Children or The Singularity is Near is more like a religious prophecy than a technological planning document.

It’s possible that building warehouse robots and email reply engines can produce the outcomes promised by Moravec and Kurzweil because we can label these activities as future making. Maybe each advance in machine computation, each iteration of software or hardware, shrinks the gap between human beings and machines. If a machine can truly answer your emails for you, is it as smart as you? Has it become a person like you? Has it made you obsolete? Possibly; but it might just mean that we’ve come to expect less and less from interpersonal communication, such that a robotic mimicry suffices for our dumbed-down expectations. More to the point, would such an email triumph mean that biological life will transition to digital life and that the future shall be the glorious age of immortal robots? Probably not. Prophetic books don’t have much track record at producing apocalyptic outcomes, but the leap from email enhancements or robot navigation to godlike machines seems like a rather greater one that its champions really address.

Dr. Robert M Geraci is Professor of Religious Studies at Manhattan College and author of Apocalyptic AI: Visions of Heaven in Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, and Robotics (Oxford University Press, 2010) and Virtually Sacred: Myth and Meaning in World of Warcraft and Second Life (Oxford University Press, 2014).