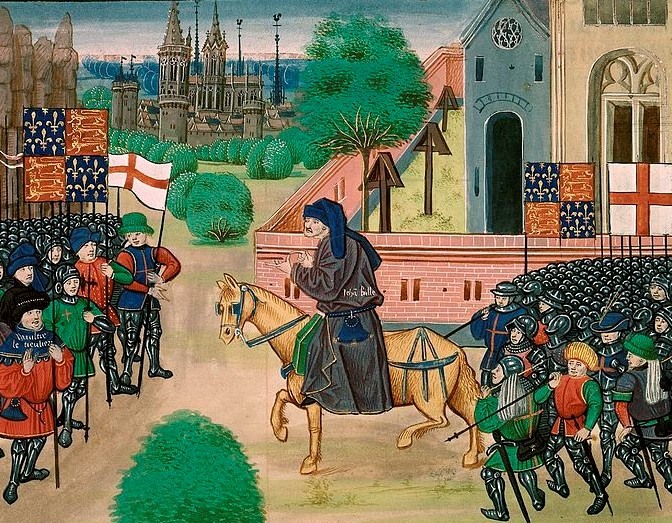

The “Peasants’ Revolt” of 1381 was an ultimately unsuccessful uprising among lower orders in England. While widespread, the uprisings have become especially associated with south-east England and London, not least because of the execution of leading figures of the realm, including the Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor of England, Simon Sudbury. The priest John Ball was a popular figure around the outbreak of the uprising in early summer 1381, and soon presented as one of the leading figures of the revolt. He was already known for his preaching against the existing secular and ecclesiastical hierarchies, and by 1381 it seems he expected the imminent transformation of the social and political order in England, with himself as the head ecclesiastical authority.

After his execution in July 1381, there was a sustained attempt to portray him as a seditious, even demonic, religious extremist whose ideas posed a threat to the nation. This portrayal dominated the history of the interpretation of Ball for four hundred years. There have been (contested) suggestions that there were less hostile, more ambiguous, or carnivalesque receptions of Ball in sixteenth-century England, such as in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part II (where Jack Cade is based on Ball) and especially the anonymous The Life and Death of Jack Straw (1593/94). Whatever sympathetic responses there may or may not have been among some sections of the audience, these plays still had to avoid censorship and there is, as we would expect, more than enough in Henry VI, Part II and The Life and Death of Jack Straw to implicate Cade and Ball as they played into anxieties about megalomaniacal religion, social disruption, and “excessive” R/reformation.

Prior to these plays, there is some firmer evidence that Ball was understood in a positive light, though not because of any levelling or rebellious concerns, and with a significant downplaying of apocalyptic tendencies that envisaged a radical transformation of the political order. Rather, he was seen as a precursor to the English Reformation and an example of the antiquity of the “true” church in England. Writing in exile in the 1540s, John Bale used the clerical title “Sir” for Ball in Image of Both Churches when he listed him among Lollard martyrs (text in Minton 2013: 186–87). Bale did not, of course, endorse the revolt and in the preface to Image of Both Churches he stressed that “In no wise rebel I here against any princely power or authority given of God.” Elsewhere, Bale denounced the two other main figures associated with the 1381 uprising—Wat Tyler and Jack Straw—and, in a common move in early modern receptions of the revolt, tried to discredit the revolt through a comparison with Anabaptism:

Jack Strawe and watte Tyler, ii, rebellyouse captaynes of the commens in the tyme of Kynge Richarde the seconde, brent all the lawers bokes, regesters, and writynges within the cytie of London, as testifyeth Johan Maior and Fabyane in their chronycles. The Anabaptystes in our tyme, an vn-quyetouse kynde of men, arrogaunt with-out measure, capcyose and vnlerned, do leaue non olde workes vnbrent, that they maye easely come by, as apered by the lybraryes at Mynster in the lande of Westphaly, whom they most furyously destroyed. (Bale 1549: 86–87)

While there were plenty of available chronicles discussing the leaders of the revolt, Bale’s reference to those of John Major and Robert Fabyan are telling because neither mention the role of Ball.

Ball-the-martyr probably came to attention of Bale through an early source hostile to Wycliffe and Lollardy, namely the Fasciculi Zizaniorum, a late fourteenth/early fifteenth-century anti-heretical collection from the Carmelite religious order. Here, Ball is presented as a close associate of Wycliffe and in opposition to transubstantiation, a polemic aimed at discrediting both Ball and Wycliffe. Bale himself formerly a Carmelite) had a copy of, and was well acquainted with, the Fasciculi Zizaniorum (Crompton 1961a; 1961b; Evenden and Freeman 2011) which, in one of many such twists in the history of the interpretation of Ball, unintentionally added legitimacy to the idea of Ball as a Lollard martyr once Bale had switched sides and became a Protestant.

But Ball as martyr was a dangerous idea in Reformation England—in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Ball was consistently presented as a seditious threat (see below). We can see how Ball was a problem for Bale’s fellow martyrologist and younger associate, John Foxe, who had access to the Fasciculi Zizaniorum through Bale. The first edition (1563) of Foxe’s Actes and Monuments cautiously notes the example of Ball, and references the anti-Ball summary from Polydore Vergil’s history (which, incidentally, inspired the common variant surname spelling, “Wall”):

About the same time or rather somewhat afore. In the yeare of our Lord M.iiiC.lxxxii. [sic] as Polidore witnesseth, there was one Iohn Balle, whome Pollidorus calleth Walle, a priest & a preacher, but only that some men do suspect, he was in the commotion of Kent against kyng Richarde in the yeare of our Lord M. iii C.lxxx. But whether this suspition were true or false, it is vncertaine, albeit Pollidorus dooth not also thinke it to be true, neither doth it seme agreable to truthe, that suche a man as he endowed with suche knowledge and vnderstandinge of the Gospell, would entermedle him selfe in anye matter so farre disagreing with the Gospell. But this surely is worthy to be noted, that when he was deliuered out of prison, afterwarde being apprehended at Couentry by Robert Treuillian, and iudged to be hanged at S. Albons, in the year of our Lord M.iiic.lxxxii. shortly after the sayd Treuillian albeit that he was chief Iustice, suffered the like punishemen, and was hanged at Tiburne, as it is thought, not without iust cause being requited for the bloud that he had shed. (1563 edition, 2.192)

Ball is not present in the later editions Foxe’s work. However, as with Bale, Ball is a notable omission in Foxe’s brief discussion of the revolt in that Ball is not mentioned precisely where he turned up in standard narratives of the revolt (1570 edition: 5.554 [cf. 5.702]; 1576 edition: 5.453; 5.575; 1583 edition: 5.597), while the leadership of the revolt in mentioned in the marginalia is associated with Jack Straw. As Susan Royal (2017: 132) points out, the silences in Foxe’s account are important. One of Foxe’s sources was one of the most influential accounts of the revolt where Ball is heavily criticised, namely that of Thomas Walsingham.

Foxe was obviously aware of the implication that Ball could potentially have been understood or misunderstood (depending on your perspective) as a martyr or a seditious rebel. This was a problem that Foxe’s contemporaries among the Tudor chroniclers tackled in different ways, such as downplaying his death or presenting him as a traitor deserving of death, each with the unambiguous assumption that Ball was emphatically not a Protestant martyr in the making (so, e.g., the chronicles associated with Holinshed, Stow, and Grafton). Other Tudor and early Jacobean interpreters (so, e.g., Thomas Cooper, Richard Bancroft, Samuel Rowlands, Thomas James) made related arguments, using Ball as a means to attack or delegitimise puritanism and the radical Reformation. In the public sphere at least, the normative understanding of Ball and 1381 was that it was excessive in its religious preferences and that this was intertwined with its seditiousness.

The examples of Bale and Foxe stand out in the late medieval and early modern history of reception of Ball. Whether this was part of a wider sympathetic reception beyond printed sources is as yet unknown and it may simply have been the case that Bale and Foxe were attracted to Ball because of their interests in the Fasciculi Zizaniorum. Moreover, this was only a reclamation of Ball based on the shared assumptions that the rebels of 1381 were emphatically wrong. As Foxe especially knew, distancing Ball from the rebels was far from easy given how central Ball was to the revolt in many of the major sources. Whatever sympathies may be detected in Tudor England, the public anti-establishment rescuing of Ball’s reputation and a preacher of dramatic social and political transformation still had to wait another two-hundred years.

References

Bale, John, 1549. The laboryouse journey & serche of John Leylande for Englandes antiquitees…enlarged: by Johan Bale. Ed. W. A. Copinger; Priory Press: Manchester, 1895.

Crompton, James. 1961a. “Fasciculi Zizaniorum I.” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 12.1: 35–45

Crompton, James. 1961b. “Fasciculi Zizaniorum II.” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 12.2: 155–66

Evenden, Elizabeth, and Thomas S. Freeman. 2011. Religion and the Book in Early Modern England: The Making of John Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Minton, Gretchen E., ed., 2013. John Bale’s ‘The Image of Both Churches.’ Dordrecht: Springer, 2013.

Royal, Susan. 2017. “English Catholics and English Heretics: The Lollards and Anti-Heresy Writing in Early Modern England.” Pp. 122–41 in James E. Kelly and Susan Royal, eds., Early Modern English Catholicism: Identity, Memory and Counter-Reformation. Leiden: Brill.

James Crossley is Academic Director of CenSAMM and author of Spectres of John Ball: The Peasants’ Revolt in English Political History 1381–2020 (Equinox, 2022).