William Blake is the largest and most important exhibition on the artist for a generation. It presents a comprehensive account of Blake’s work as an artist, showing over 300 works from throughout his career, and in multiple media – paintings, watercolours, drawings, commercial engravings and Blake’s various innovative forms of printmaking. Among the exhibits are rarely seen items from private collections, and loans from the US and Australia, so this will be a once in a lifetime opportunity to see many of the items on display.

Its focus is emphatically art historical, attending to matters such as techniques, materials, prices paid, patrons, and circumstances of display. This approach is much needed, as it situates Blake in the art world of his time, demonstrating that, while not a central figure in the art world of his time, nor was he an outsider to that sphere as he has often been presented to be.

Interpretation of the symbolism of Blake’s images is avoided, and instead captions focus on matters such as bindings, frames, and materials. Occasionally, the curators allude to scholarly debate about the meanings of Blake’s works, but do not get bogged down in unpacking these discussions. Thus, while the exhibition includes plenty of works that will be of interest to CenSAMM readers, there is little by way of interpretation that illuminates Blake’s apocalypticism. Visitors are instead left to draw their own conclusions on Blake’s symbolism. This post, then, is less a review in the conventional sense, and more something a visitors’ guide to apocalyptic and millenarian works in the exhibition.

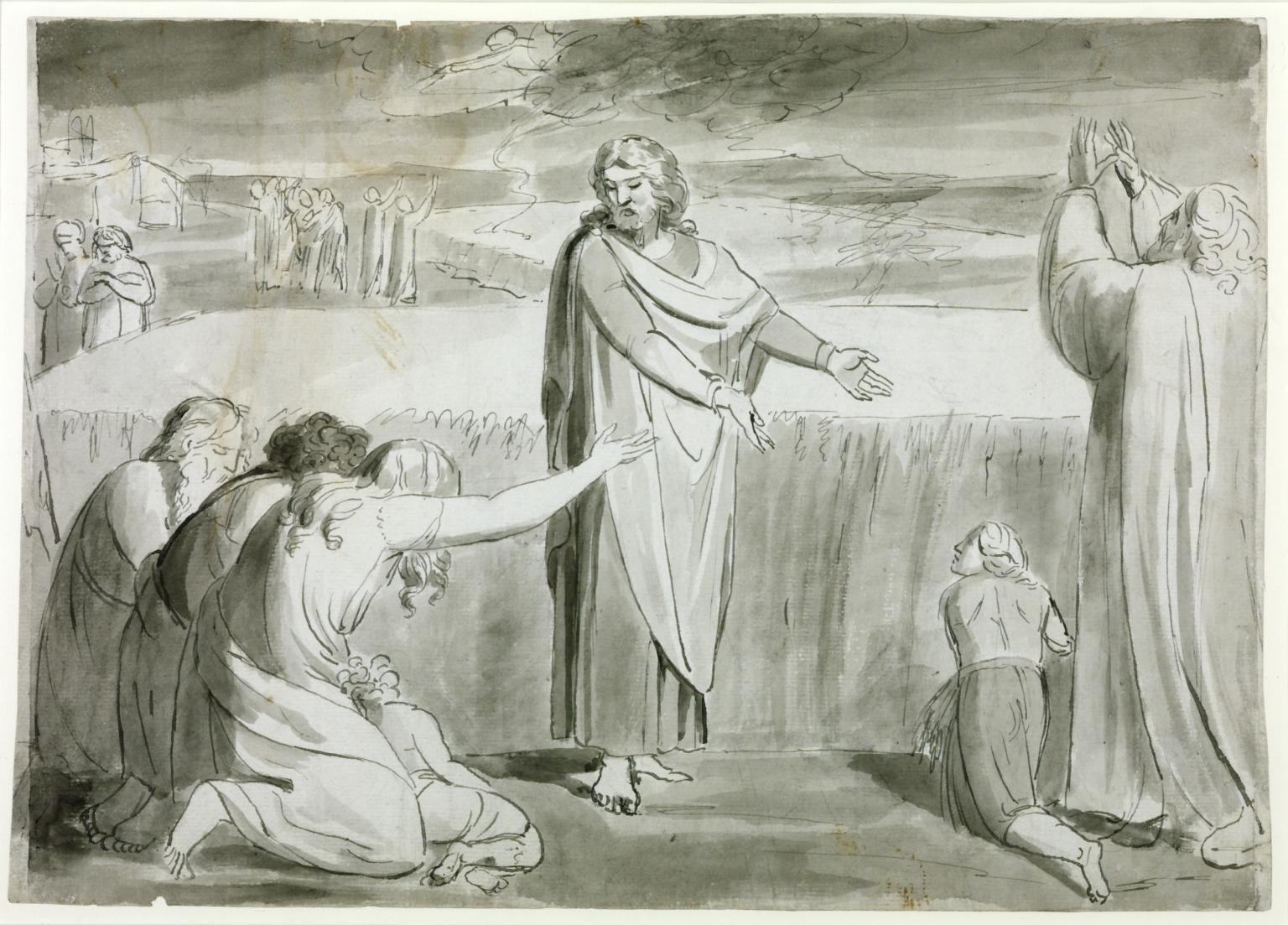

The first room focuses on the period of and after Blake’s training at the Royal Academy Schools, which he entered in 1779. From this early stage in his career, there is evidence of Blake’s interest in apocalyptic subjects. The drawing known as The Good Farmer, Probably the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares (c.1780–5, Tate) is one of a group of seven interrelated compositions that relate to Jesus’ parables on the theme of harvest in which the fruitfulness or otherwise of seed sown is a metaphor for the spiritual condition of mankind: some flourish whilst others wilt or are like weeds. In the Tate drawing, Jesus stands in front of a field of grain in the centre foreground, flanked by supplicant figures. Whatever the exact biblical source(s) of this drawing and related compositions (not exhibited), as a group they represent sustained reflection on apocalyptic themes of harvest and destruction, resonating with millenarian themes of war and destruction in other works of the period by the artist, such as his Pestilence and War drawings (c.1779–1805). One of the later Pestilence drawings is shown in the next room (c.1795–1800, Bristol Museums & Art Gallery). Such subjects can be seen as Blake’s response to turbulent contemporaneous events such as the American Revolutionary War (1775–83) and the Gordon Riots (1780), and later the French Revolution (1789–99).

The second room explores Blake as a printmaker, both as a commercial engraver, and as a maker of illuminated books, with a particular focus on the 1790s. Examples of many of Blake’s prophetic books from this period are displayed here, as well as what is probably his best-known work in this medium Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789, 1794). There is plenty to interest CenSAMM readers here, including copies of America (1793) and Europe (1794), which present the American and French Revolutions as augurs of the apocalypse.

Next, the exhibition considers Blake’s patrons. Notable here is the civil servant Thomas Butts, who purchased some 200 works from Blake, including two series of biblical designs – in tempera and watercolour. The watercolour series includes some of Blake’s best-known apocalyptic images, including ten subjects from Revelation, two of which are exhibited here: The Great Dragon and the Beast from the Sea (c.1803–5, National Gallery of Art) and The Number of the Beast is 666 (c.1805, The Rosenbach). This reunion of two of the four dispersed Red Dragon group is particularly striking. Also of interest here is a series of six watercolours illustrating John Milton’s On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity (1809, The Whitworth), painted for Revd Joseph Thomas, in which the birth of Christ results in the overthrow of pagan deities. These unusual nativity images, which show the downfall of the pagan deities, present the birth of Christ as an apocalyptic event.

A final highlight in the patrons section is A Vision of the Last Judgement (c.1808, Petworth House), painted for Elizabeth Ilive, Countess Egremont. This watercolour is one of a number of related compositions by Blake that culminated in a lost monumental painting that he worked on in the final two decades of his life. Blake also wrote two explanations of the subject – one for the Petworth picture (1808), and a longer version for the lost painting (c.1810). The latter document in particular is important for understanding Blake’s theory of art and apocalyptic vision. In it, he explains: ‘whenever any Individual Rejects Error & Embraces Truth a Last Judgment passes upon that Individual.’ This statement encapsulates the central tenet of Blake’s personal vision: in all things, we should strive to reject error and embrace truth, and to do so is apocalyptic. The Last Judgement is not something that happens (only) at the end of time; it is constantly occurring when an individual rejects error and embraces truth. Blake also tells us how he hopes to facilitate that process for his audience through his art; in the same document he writes:

If the Spectator could Enter into these Images in his Imagination … then would he arise from his Grave then would he meet the Lord in the Air & then he would be happy

In other words, Blake wants his images to engender a last judgement for the viewer.

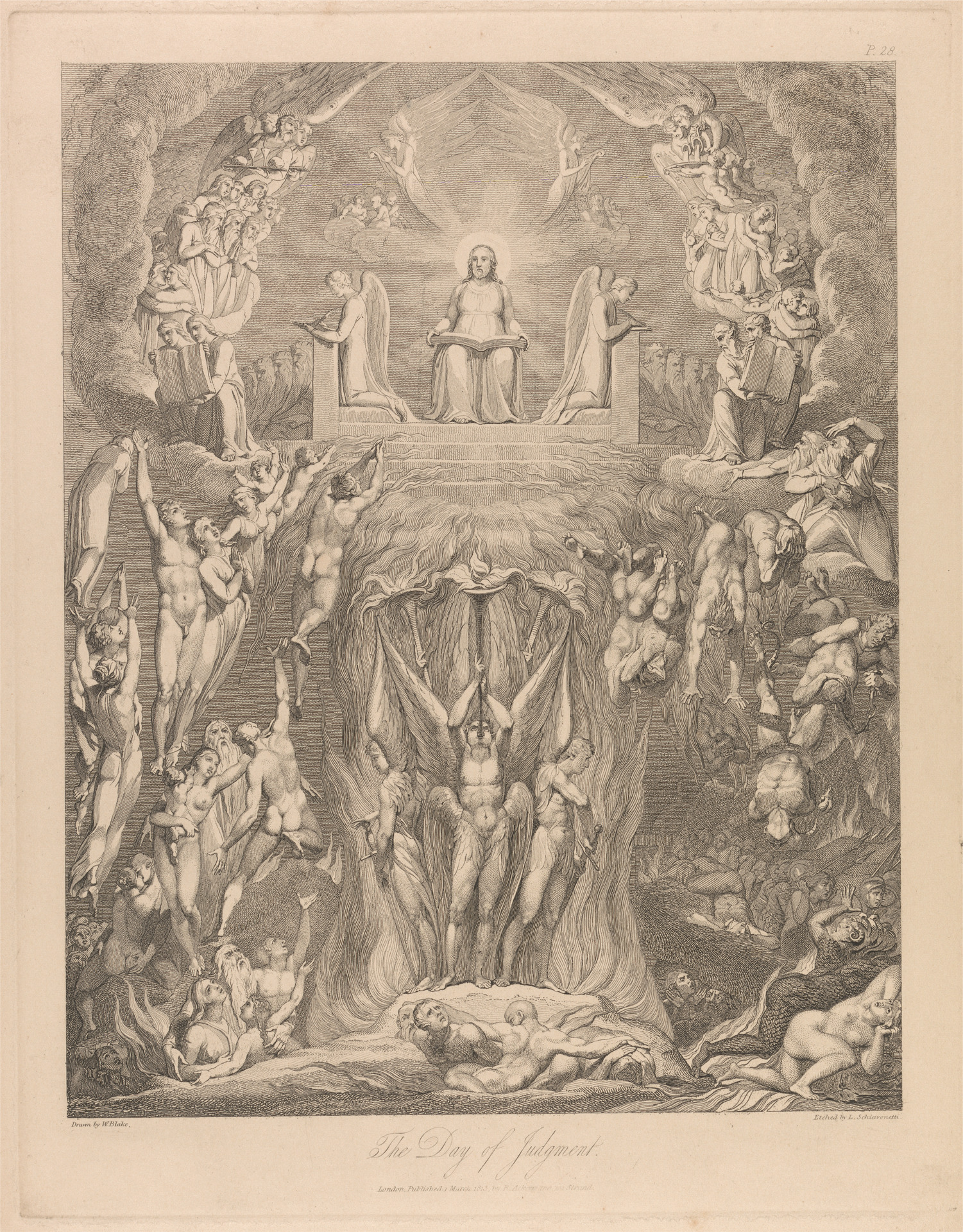

Room 4 explores the decade from 1805, which was a difficult period for Blake. A highlight here is a group of watercolour designs for Robert Blair’s The Grave, reuniting works that were dispersed in 2006. These designs were commissioned by the publisher Robert Cromek in 1805 for Blair’s poem on death and the afterlife. Blake expected to have the work of engraving the plates for publication, as well as creating the designs, but Cromek was not happy with the trial plate that Blake produced (the only surviving print of which is shown here) and instead engaged the fashionable printmaker Luigi Schiavonetti to engrave Blake’s design, much to the artist’s chagrin. Among the watercolours are Christ Descending Into the Grave (c.1805–7, private collection), which became the frontispiece to Cromek’s edition. Several copies of the book, opened to different plates, are also shown here; of particular interest here is The Day of Judgement, which is the first version of the composition that Blake subsequently developed in A Vision of the Last Judgement seen in the previous room.

This part of the exhibition also includes two innovative curatorial devices to evoke the contexts in which Blake himself exhibited and hoped to exhibit his work. First, there is a reconstruction of Blake’s disastrous one-man show of 1809 in a space that evokes the sort of eighteenth-century domestic interior in which it took place. Beyond, there are evocations of Blake’s unrealised ambitions to paint on a grand scale, via projections and a mock-up photograph of one of the biblical watercolours as an altarpiece in Blake’s family church, St James’ Piccadilly.

Save stamina for the final room, because it is particularly rich in works that will be of interest to CenSAMM readers. In the final years of his life (he died in 1827), in large part thanks to the support of the younger artist John Linnell, Blake pursued several ambitious projects. Highlights here include nineteen of Blake’s 102 watercolours for Dante’s Divine Comedy (1824–7), which deal with themes of judgement. The series was dispersed in the twentieth century, and this display reunites a selection from the Tate, The Ashmolean Museum, The British Museum, and the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

From the same years is the Pilgrims’ Progress series (private collection); 27 of the 29 watercolours are shown here. Recording Christian’s journey to the Celestial City, the theme of Bunyan’s narrative resonates with Blake’s own accounts of spiritual journeys in Milton, A Poem (c.1804–11) and Jerusalem, the Emanation of the Giant Albion (1804–c.1820). 25 plates from the rarely-seen Copy B of Jerusalem (private collection) – one of only two fully-coloured copies – are also shown here. As seen above, Blake wanted his art to engender the spiritual progress of his reader-viewer, in order to bring about their individual last judgement. That is the central theme of Jerusalem, which tells the story of the fall and awakening of its protagonist Albion, concluding with union of all living things into one Divine Body.

If you go to this exhibition expecting of a narrative about Blake’s apocalyptic vision you will be disappointed. What you will encounter, however, is a rich display of Blake’s works that engage with that theme, many of which may not be shown again in the UK for decades. Plenty has been written on Blake’s apocalyptic vision elsewhere, so do your homework, and then enjoy this opportunity to encounter some of Blake’s most powerful works.

William Blake is at Tate Britain until 2 February 2020.

Naomi Billingsley is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Manchester. She is the author of The Visionary Art of William Blake: Christianity, Romanticism and the Pictorial Imagination (London, 2018).

A related review of the exhibition by Naomi will appear in Art and Christianity, No. 100 in late 2019.